Life Is Glimpsed through the Night Windows

As we approach the winter solstice and the shortest day of the year, when darkness creeps in before we’ve had a chance to savor the sun, we spend more time navigating our city by artificial light. Streetlights flicker on before work days are over; cars turn on their headlights before we’ve made it home to make dinner. And on those walks through residential blocks and dense neighborhoods of commerce, light comes through the windows.

It is easy to take our illuminated modern lives for granted after twilight. Tallow candles, kerosene lamps, and fires in hearths once lit homes in New York; gaslight arrived on the streets in the 19th century. Later came the arc lamps radiating over Broadway by late 1880. The shift to widespread electricity was sparked on September 4, 1882, when the Edison Illuminating Company on Pearl Street—considered the first of the commercial power stations—switched on, leading to the new power rapidly overtaking gas. That year, Edward H. Johnson, a partner in Edison’s company, draped his Christmas tree with 80 hand-wired electric lights colored red, white, and blue and invited people to witness the brilliant spectacle in his Murray Hill home.

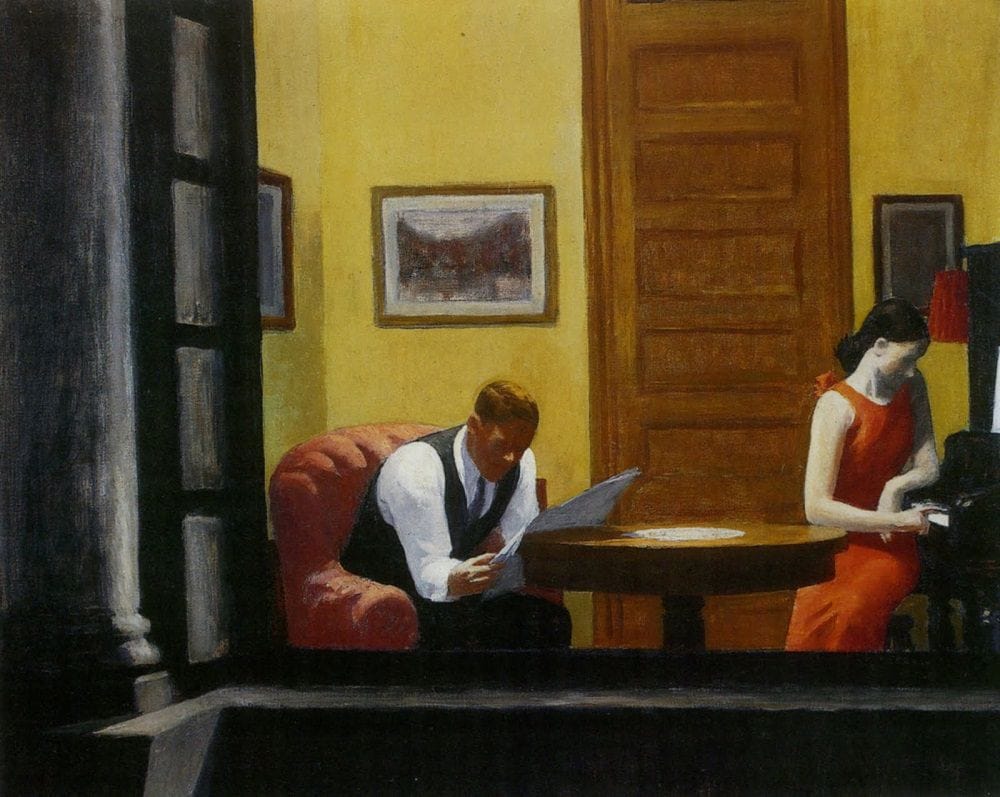

Now Christmas trees, menorahs, tangles of festive lights, and wreaths are displayed in windows across the city, luminous after sunset. In these brief days, with their low temperatures that encourage brisk walks from one destination to the next, there is more life than at any other time of year to pause and view from the street. Skyscrapers seen from elevated tracks display mazes of cubicles where stray coffee cups and solitary late workers are illuminated like Macy’s windows; brownstones with bay windows provide glimpses of enviable built-in bookshelves and potted plants overtaking corners. Glass storefronts of bodegas and pizza slice shops become incandescent portals into neighborhood life. Silhouettes of cats stand guard behind window panes like sentinels; restless dogs press their noses to windows cracked open to let some of the radiator heat escape a sweltering apartment.

It is cold and dark outside, but take your time to observe what’s around you, where lives stacked up in apartments and offices and businesses are all revealed. (Don’t be too nosy about it; keep your pace and do not stare too long.) As another year is ending, it seems like there is never enough time to do what needs to be done. But here we are all together, millions of us in the city, trying to shape what time we have into lives and meaning through these flickering moments.

- There are a few places in the city where you are invited to be a voyeur for a moment. At IFC on Sixth Avenue, two peepholes allow passersby to look into a theater and catch a glimpse of a movie. A peephole above the Atlantic Avenue-Barclays Center subway station in Brooklyn offers a look at a sculpture by George Trakas suspended over the commuter stairs. Tiny windows on the doors to Saint Patrick’s Old Cathedral Churchyard on Mulberry Street reveal a view of the old graves.

- The color of the city at night has changed with each new lighting innovation. With hundreds of thousands of streetlights recently converted to LEDs, gone is the bright yellow-orange of sodium vapor. Now the frosty glow of white marks streets and park pathways. What does this change about the character of the city? Will future period films set in the early 2000s have to pay attention to this quality of a night where streetlights flare a fiery color instead of cold tones?

- At the Gasnick Supply hardware store on Second Avenue, the fourth-longest-lasting light bulb known to exist blazed from 1912 well into the 20th century. As reported in 1983, the owner, Jack Gasnick, was irked by the Guinness Book of World Records overlooking his bulb in favor of one in a California firehouse. “They’d be darn fools not to,” he said at the time about recognizing his store’s electrical landmark. Roadside America states that Gasnick’s store was razed in 2003 for the construction of new condos, yet the mystery of the bulb’s fate remains: “Did Gasnick take his bulb with him—or was it still burning when the power was cut off and the wrecking ball arrived? It was a tough old bulb; who knows? Perhaps it lies buried under tons of rubble, patiently waiting for some future civilization to dig it up and screw it into a working socket.”